History

Jacques de Molay

Jacques de Molay (c. 1243 – 18 March 1314), also spelled "Molai", was the 23rd and last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, leading the Order from 20 April 1298 until it was dissolved by order of Pope Clement V in 1312. Though little is known of his actual life and deeds except for his last years as Grand Master, he is one of the best known Templars. Jacques de Molay's goal as Grand Master was to reform the Order, and adjust it to the situation in the Holy Land during the waning days of the Crusades. As European support for the Crusades had dwindled, other forces were at work which sought to disband the Order and claim the wealth of the Templars as their own. King Philip IV of France, deeply in debt to the Templars, had Molay and many other French Templars arrested in 1307 and tortured into making false confessions. When Molay later retracted his confession, Philip had him burned upon a scaffold on an island in the River Seine in front of Notre Dame de Paris in March, 1314. The sudden end of both the centuries-old order of Templars and the dramatic execution of its last leader turned Molay into a legendary figure. Little is known of his early years, but Jacques de Molay was probably born in Molay, Haute-Saône, in the County of Burgundy, at the time a territory ruled by Otto III as part of the Holy Roman Empire, and in modern times in the area of Franche-Comté, northeastern France. His birth year is not certain, but judging by statements made during the later trials, was probably around 1250. He was born, as most Templar knights were, into a family of minor or middle-ranking nobility. It is suggested that he was dubbed a knight at age 21 in 1265 and is known that he was executed in 1314, aged about 70. If correct, these dates lead to the belief that he was born about 1244. In 1265, as a young man, he was received into the Order of the Templars in a chapel at the Beaune House, by Humbert de Pairaud, the Visitor of France and England. Another prominent Templar in attendance was Amaury de la Roche, Templar Master of the province of France. Around 1270, Molay went to the East (Outremer), although little is recorded of his activities for the next twenty years.Grand Master

After the Fall of Acre to the Egyptian Mamluks in 1291, the Franks (a name used in the Levant for Catholic Europeans) who were able to do so retreated to the island of Cyprus. It became the headquarters of the dwindling Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the base of operations for any future military attempts by the Crusaders against the Egyptian Mamluks, who for their part were systematically conquering any last Crusader strongholds on the mainland. Templars in Cyprus included Jacques de Molay and Thibaud Gaudin, their 22nd Grand Master. During a meeting assembled on the island in the autumn of 1291, Molay spoke of reforming the Order and put himself forward as an alternative to the current Grand Master. Gaudin died around 1292 and, as there were no other serious contenders for the role at the time, Molay was soon elected. In spring 1293, he began a tour of the West to try to muster more support for a reconquest of the Holy Land. Developing relationships with European leaders such as Pope Boniface VIII, Edward I of England, James I of Aragon and Charles II of Naples, Molay's immediate goals were to strengthen the defence of Cyprus and rebuild the Templar forces. From his travels, he was able to secure authorization from some monarchs for the export of supplies to Cyprus, but could obtain no firm commitment for a new Crusade. There was talk of merging the Templars with one of the other military orders, the Knights Hospitaller. The Grand Masters of both orders opposed such a merger, but pressure increased from the Papacy. It is known that Molay held two general meetings of his order in southern France, at Montpellier in 1293 and at Arles in 1296, where he tried to make reforms. In the autumn of 1296, Molay was back in Cyprus to defend his Order against the interests of Henry II of Cyprus, which conflict had its roots back in the days of Guillaume de Beaujeu. From 1299 to 1303, Molay was engaged in planning and executing a new attack against the Mamluks. The plan was to coordinate actions between the Christian military orders, the King of Cyprus, the nobility of Cyprus, the forces of Cilician Armenia, and a new potential ally, the Mongols of the Ilkhanate (Persia), to oppose the Egyptian Mamluks and take back the coastal city of Tortosa in Syria. Ghazan, the Mongol ruler of the Ilkhanate, sought a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Crusaders against the Egyptian Mamluks, but was never able to successfully coordinate military actions For generations, there had been communications between the Mongols and Europeans towards the possibility of forging a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Mamluks, but without success. The Mongols had been repeatedly attempting to conquer Syria themselves, each time either being forced back by the Egyptian Mamluks or having to retreat because of a civil war within the Mongol Empire, such as having to defend from attacks from the Mongol Golden Horde to the north. In 1299, the Ilkhanate again attempted to conquer Syria, having some preliminary success against the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in December 1299. In 1300, Molay and other forces from Cyprus put together a small fleet of sixteen ships which committed raids along the Egyptian and Syrian coasts. The force was commanded by King Henry II of Jerusalem, the king of Cyprus, accompanied by his brother, Amalric, Lord of Tyre, and the heads of the military orders, with the ambassador of the Mongol leader Ghazan also in attendance. The ships left Famagusta on 20 July 1300, and under the leadership of Admiral Baudouin de Picquigny, raided the coasts of Egypt and Syria: Rosetta, Alexandria, Acre, Tortosa and Maraclea, before returning to Cyprus. The Cypriots then prepared for an attack on Tortosa in late 1300, sending a joint force to a staging area on the island of Ruad, from which raids were launched on the mainland. The intent was to establish a Templar bridgehead to await assistance from Ghazan's Mongols, but the Mongols failed to appear in 1300. The same happened in 1301 and 1302, and the island was finally lost in the Siege of Ruad on 26 September 1302, eliminating the Crusaders' last foothold near the mainland. Following the loss of Ruad, Molay abandoned the tactic of small advance forces, and instead put his energies into trying to raise support for a new major Crusade, as well as strengthening Templar authority in Cyprus. When a power struggle erupted between King Henry II and his brother Amalric, the Templars supported Amalric, who took the crown and had his brother exiled in 1306. Meanwhile, pressure increased in Europe that the Templars should be merged with the other military orders, perhaps all placed under the authority of one king, and that individual should become the new King of Jerusalem when it was conquered.Travel to France

In 1305, the newly elected Pope Clement V asked the leaders of the military orders for their opinions concerning a new crusade and the merging of their orders. Molay was asked to write memoranda on each of the issues, which he did during the summer of 1306. Molay was opposed to the merger, believing instead that having separate military orders was a stronger position, as the missions of each order were somewhat different. He was also of the belief that if there were to be a new crusade, it needed to be a large one, as the smaller attempts were not effective. On 6 June, the leaders of both the Templars and the Hospitallers were officially asked to come to the Papal offices in Poitiers to discuss these matters, with the date of the meeting scheduled as All Saints Day in 1306, though it later had to be postponed due to the Pope's illness with gastro-enteritis. Molay left Cyprus on 15 October, arriving in France in late 1306 or early 1307; however, the meeting was again delayed until late May due to the Pope's illness. King Philip IV of France, deeply in debt to the Templars, was in favour of merging the Orders under his own command, thereby making himself Rex Bellator, or War King. Molay, however, rejected the idea. Philip was already at odds with the papacy, trying to tax the clergy, and had been attempting to assert his own authority as higher than that of the Pope. For this, one of Clement's predecessors, Pope Boniface VIII, had attempted to have Philip excommunicated, but Philip then had Boniface abducted and charged with heresy. The elderly Boniface was rescued, but then died of shock shortly thereafter. His successor Pope Benedict XI did not last long, dying in less than a year, possibly poisoned via Philip's councillor Guillaume de Nogaret. It took a year to choose the next Pope, the Frenchman Clement V, who was also under strong pressure to bend to Philip's will. Clement moved the Papacy from Italy to Poitiers, France, where Philip continued to assert more dominance over the Papacy and the Templars. The Grand Master of the Hospitallers, Fulk de Villaret, was also delayed in his travel to France, as he was engaged with a battle at Rhodes. He did not arrive until late summer, so while waiting for his arrival, Molay met the Pope to discuss other matters, one of which was the charges by one or more ousted Templars who had made accusations of impropriety in the Templars' initiation ceremony. Molay had already spoken with the king in Paris on 24 June 1307 about the accusations against his order and was partially reassured. Returning to Poitiers, Molay asked the Pope to set up an inquiry to quickly clear the Order of the rumours and accusations surrounding it, and the Pope convened an inquiry on 24 August.Arrest and charges

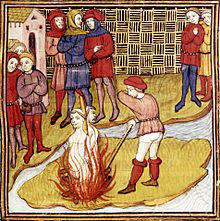

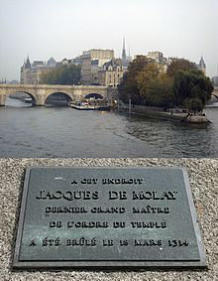

There were five initial charges lodged against the Templars. The first was renunciation of and spitting on the cross during initiation into the Order. The second was the stripping of the man to be initiated and the thrice kissing of that man by the preceptor on the navel, posterior and mouth. The third was telling the neophyte (novice) that unnatural lust was lawful and indulged in commonly. The fourth was that the cord worn by the neophyte day and night was consecrated by wrapping it around an idol in the form of a human head with a great beard, and that this idol was adored in all chapters. The fifth was that the priests of the order did not consecrate the host in celebrating Mass. Subsequently, the charges would be increased and would become, according to the procedures, lists of articles 86 to 127 in which will be added a few other charges, such as the prohibition to priests who do not belong to the order. On 14 September, Philip took advantage of the rumours and inquiry to begin his move against the Templars, sending out a secret order to his agents in all parts of France to implement a mass arrest of all Templars at dawn on 13 October. Philip wanted the Templars arrested and their possessions confiscated to incorporate their wealth into the Royal Treasury and to be free of the enormous debt he owed the Templar Order. Molay was in Paris on 12 October, where he was a pallbearer at the funeral of Catherine of Courtenay, wife of Count Charles of Valois, and sister-in-law of King Philip. In a dawn raid on Friday, 13 October 1307, Molay and sixty of his Templar brother knights were arrested. Philip then had the Templars charged with heresy and many other trumped-up charges, most of which were identical to the charges which had previously been leveled by Philip's agents against Pope Boniface VIII. During forced interrogation by royal agents at the University of Paris on 24, or 25 October, Molay confessed that the Templar initiation ritual included "denying Christ and trampling on the Cross". He was also forced to write a letter asking every Templar to admit to these acts. Under pressure from Philip IV, Pope Clement V ordered the arrest of all the Templars throughout Christendom. Jacques de Molay sentenced to the stake in 1314, from the Chronicle of France or of St Denis (fourteenth century). Note the shape of the island, representing the Île de la Cité (Island of the City) in the Seine, where the executions took place. The pope still wanted to hear Molay's side of the story, and dispatched two cardinals to Paris in December 1307. In front of the cardinals, Molay retracted his earlier confessions. A power struggle ensued between the king and the pope, which was settled in August 1308 when they agreed to split the convictions. Through the papal bull Faciens misericordiam, the procedure to prosecute the Templars was set out on a duality, whereby one commission would judge individuals of the Order and a different commission would judge the Order as a whole. Pope Clement called for an ecumenical council to meet in Vienne in 1310 to decide the future of the Templars. In the meantime, the Order's dignitaries, among them Molay, were to be judged by the pope. In the royal palace at Chinon, Molay was again questioned by the cardinals, but this time with royal agents present, and he returned to his forced admissions made in 1307. In November 1309, the Papal Commission for the Kingdom of France began its own hearings, during which Molay again recanted, stating that he did not acknowledge the accusations brought against his order. Marker at the site of Jacques de Molay's execution in Paris. (Translation: At this location, Jacques de Molay, last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, was burned on 18 March 1314), located by the stairs from the Pont-Neuf bridge. The top half of this photo shows the part of the island where the executions took place. The lower half shows the plaque, which is on one of the pillars of the bridge, behind the trees. Any further opposition by the Templars was effectively broken when Philip used the previously forced confessions to sentence 54 Templars to be burnt at the stake on 10–12 May 1310. The council which had been called by the Pope for 1310 was delayed for a further two years due to the length of the trials, but was finally convened in 1312. On 22 March 1312, at the Council of Vienne, the Order of the Knights Templar was abolished by papal decreeDeath

Of Molay's death, Henry Charles Lea gives this account: "The cardinals dallied with their duty until 18 March 1314, when, on a scaffold in front of Notre Dame, Jacques de Molay, Templar Grand Master, Geoffroi de Charney, Master of Normandy, Hugues de Peraud, Visitor of France, and Godefroi de Gonneville, Master of Aquitaine, were brought forth from the jail in which for nearly seven years they had lain, to receive the sentence agreed upon by the cardinals, in conjunction with the Archbishop of Sens and some other prelates whom they had called in. Considering the offences which the culprits had confessed and confirmed, the penance imposed was in accordance with rule — that of perpetual imprisonment. The affair was supposed to be concluded when, to the dismay of the prelates and wonderment of the assembled crowd, Jacques de Molay and Geoffroi de Charney arose. They had been guilty, they said, not of the crimes imputed to them, but of basely betraying their Order to save their own lives. It was pure and holy; the charges were fictitious and the confessions false. Hastily the cardinals delivered them to the Prevot of Paris, and retired to deliberate on this unexpected contingency, but they were saved all trouble. When the news was carried to Philippe he was furious. A short consultation with his council only was required. The canons pronounced that a relapsed heretic was to be burned without a hearing; the facts were notorious and no formal judgement by the papal commission need be waited for. That same day, by sunset, a pile was erected on a small island in the Seine, the Ile des Juifs, near the palace garden. There de Molay, de Charney, de Gonneville, and de Peraud were slowly burned to death, refusing all offers of pardon for retraction, and bearing their torment with a composure which won for them the reputation of martyrs among the people, who reverently collected their ashes as relics." (Note: the account varies by one day, not unusual for chronicles of the middle ages) Chinon Parchment Main article: Chinon Parchment In September 2001, Barbara Frale found a copy of the Chinon Parchment in the Vatican Secret Archives, a document which explicitly confirms that in 1308 Pope Clement V absolved Jacques de Molay and other leaders of the Order including Geoffroi de Charney and Hugues de Pairaud. She published her findings in the Journal of Medieval History in 2004. Another Chinon parchment dated 20 August 1308 addressed to Philip IV of France, well-known to historians, stated that absolution had been granted to all those Templars that had confessed to heresy "and restored them to the Sacraments and to the unity of the Church".

Chapel of the Beaune

Commandery nowadays, where

Jacques de Molay was ordinated.

The Grand Master of the Hospitallers,

Fulk de Villaret

Thibaud

Gaudin

(1229?

–

April

16,

1292)

was

the

Grand

Master

of

the

Knights

Templar

from

August

1291

until his death in April 1292.

In

Solo

Deo

Salus

-

Salvation

In

God

Alone

P

ope

Clement

V

(Latin:

Clemens

V;

c.

1264

–

20

April

1314),

born

Raymond

Bertrand

de

Got

(also

occasionally

spelled

de

Guoth

and

de

Goth),

was

Pope

from

5

June

1305

to

his

death

in

1314.

He

is

remembered

for

suppressing

the

order

of

the

Knights

Templar

and

allowing

the

execution

of

many

of

its

members,

and

as

the

Pope

who

moved

the

Papacy

from

Rome

to

Avignon,

ushering

in

the

period

known

as the Avignon Papacy.

King Philip IV of France

Chinon Parchment

KNIGHTS TEMPLAR

A video with Knights Oath and

Templars Oath.

© 2020 Knights Templar- All Rights Reserved

SOC Templar Knights

History

Jacques de Molay

Jacques de Molay (c. 1243 – 18 March 1314), also spelled "Molai", was the 23rd and last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, leading the Order from 20 April 1298 until it was dissolved by order of Pope Clement V in 1312. Though little is known of his actual life and deeds except for his last years as Grand Master, he is one of the best known Templars. Jacques de Molay's goal as Grand Master was to reform the Order, and adjust it to the situation in the Holy Land during the waning days of the Crusades. As European support for the Crusades had dwindled, other forces were at work which sought to disband the Order and claim the wealth of the Templars as their own. King Philip IV of France, deeply in debt to the Templars, had Molay and many other French Templars arrested in 1307 and tortured into making false confessions. When Molay later retracted his confession, Philip had him burned upon a scaffold on an island in the River Seine in front of Notre Dame de Paris in March, 1314. The sudden end of both the centuries-old order of Templars and the dramatic execution of its last leader turned Molay into a legendary figure. Little is known of his early years, but Jacques de Molay was probably born in Molay, Haute-Saône, in the County of Burgundy, at the time a territory ruled by Otto III as part of the Holy Roman Empire, and in modern times in the area of Franche-Comté, northeastern France. His birth year is not certain, but judging by statements made during the later trials, was probably around 1250. He was born, as most Templar knights were, into a family of minor or middle-ranking nobility. It is suggested that he was dubbed a knight at age 21 in 1265 and is known that he was executed in 1314, aged about 70. If correct, these dates lead to the belief that he was born about 1244. In 1265, as a young man, he was received into the Order of the Templars in a chapel at the Beaune House, by Humbert de Pairaud, the Visitor of France and England. Another prominent Templar in attendance was Amaury de la Roche, Templar Master of the province of France. Around 1270, Molay went to the East (Outremer), although little is recorded of his activities for the next twenty years.Grand Master

After the Fall of Acre to the Egyptian Mamluks in 1291, the Franks (a name used in the Levant for Catholic Europeans) who were able to do so retreated to the island of Cyprus. It became the headquarters of the dwindling Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the base of operations for any future military attempts by the Crusaders against the Egyptian Mamluks, who for their part were systematically conquering any last Crusader strongholds on the mainland. Templars in Cyprus included Jacques de Molay and Thibaud Gaudin, their 22nd Grand Master. During a meeting assembled on the island in the autumn of 1291, Molay spoke of reforming the Order and put himself forward as an alternative to the current Grand Master. Gaudin died around 1292 and, as there were no other serious contenders for the role at the time, Molay was soon elected. In spring 1293, he began a tour of the West to try to muster more support for a reconquest of the Holy Land. Developing relationships with European leaders such as Pope Boniface VIII, Edward I of England, James I of Aragon and Charles II of Naples, Molay's immediate goals were to strengthen the defence of Cyprus and rebuild the Templar forces. From his travels, he was able to secure authorization from some monarchs for the export of supplies to Cyprus, but could obtain no firm commitment for a new Crusade. There was talk of merging the Templars with one of the other military orders, the Knights Hospitaller. The Grand Masters of both orders opposed such a merger, but pressure increased from the Papacy. It is known that Molay held two general meetings of his order in southern France, at Montpellier in 1293 and at Arles in 1296, where he tried to make reforms. In the autumn of 1296, Molay was back in Cyprus to defend his Order against the interests of Henry II of Cyprus, which conflict had its roots back in the days of Guillaume de Beaujeu. From 1299 to 1303, Molay was engaged in planning and executing a new attack against the Mamluks. The plan was to coordinate actions between the Christian military orders, the King of Cyprus, the nobility of Cyprus, the forces of Cilician Armenia, and a new potential ally, the Mongols of the Ilkhanate (Persia), to oppose the Egyptian Mamluks and take back the coastal city of Tortosa in Syria. Ghazan, the Mongol ruler of the Ilkhanate, sought a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Crusaders against the Egyptian Mamluks, but was never able to successfully coordinate military actions For generations, there had been communications between the Mongols and Europeans towards the possibility of forging a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Mamluks, but without success. The Mongols had been repeatedly attempting to conquer Syria themselves, each time either being forced back by the Egyptian Mamluks or having to retreat because of a civil war within the Mongol Empire, such as having to defend from attacks from the Mongol Golden Horde to the north. In 1299, the Ilkhanate again attempted to conquer Syria, having some preliminary success against the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in December 1299. In 1300, Molay and other forces from Cyprus put together a small fleet of sixteen ships which committed raids along the Egyptian and Syrian coasts. The force was commanded by King Henry II of Jerusalem, the king of Cyprus, accompanied by his brother, Amalric, Lord of Tyre, and the heads of the military orders, with the ambassador of the Mongol leader Ghazan also in attendance. The ships left Famagusta on 20 July 1300, and under the leadership of Admiral Baudouin de Picquigny, raided the coasts of Egypt and Syria: Rosetta, Alexandria, Acre, Tortosa and Maraclea, before returning to Cyprus. The Cypriots then prepared for an attack on Tortosa in late 1300, sending a joint force to a staging area on the island of Ruad, from which raids were launched on the mainland. The intent was to establish a Templar bridgehead to await assistance from Ghazan's Mongols, but the Mongols failed to appear in 1300. The same happened in 1301 and 1302, and the island was finally lost in the Siege of Ruad on 26 September 1302, eliminating the Crusaders' last foothold near the mainland. Following the loss of Ruad, Molay abandoned the tactic of small advance forces, and instead put his energies into trying to raise support for a new major Crusade, as well as strengthening Templar authority in Cyprus. When a power struggle erupted between King Henry II and his brother Amalric, the Templars supported Amalric, who took the crown and had his brother exiled in 1306. Meanwhile, pressure increased in Europe that the Templars should be merged with the other military orders, perhaps all placed under the authority of one king, and that individual should become the new King of Jerusalem when it was conquered.Travel to France

In 1305, the newly elected Pope Clement V asked the leaders of the military orders for their opinions concerning a new crusade and the merging of their orders. Molay was asked to write memoranda on each of the issues, which he did during the summer of 1306. Molay was opposed to the merger, believing instead that having separate military orders was a stronger position, as the missions of each order were somewhat different. He was also of the belief that if there were to be a new crusade, it needed to be a large one, as the smaller attempts were not effective. On 6 June, the leaders of both the Templars and the Hospitallers were officially asked to come to the Papal offices in Poitiers to discuss these matters, with the date of the meeting scheduled as All Saints Day in 1306, though it later had to be postponed due to the Pope's illness with gastro- enteritis. Molay left Cyprus on 15 October, arriving in France in late 1306 or early 1307; however, the meeting was again delayed until late May due to the Pope's illness. King Philip IV of France, deeply in debt to the Templars, was in favour of merging the Orders under his own command, thereby making himself Rex Bellator, or War King. Molay, however, rejected the idea. Philip was already at odds with the papacy, trying to tax the clergy, and had been attempting to assert his own authority as higher than that of the Pope. For this, one of Clement's predecessors, Pope Boniface VIII, had attempted to have Philip excommunicated, but Philip then had Boniface abducted and charged with heresy. The elderly Boniface was rescued, but then died of shock shortly thereafter. His successor Pope Benedict XI did not last long, dying in less than a year, possibly poisoned via Philip's councillor Guillaume de Nogaret. It took a year to choose the next Pope, the Frenchman Clement V, who was also under strong pressure to bend to Philip's will. Clement moved the Papacy from Italy to Poitiers, France, where Philip continued to assert more dominance over the Papacy and the Templars. The Grand Master of the Hospitallers, Fulk de Villaret, was also delayed in his travel to France, as he was engaged with a battle at Rhodes. He did not arrive until late summer, so while waiting for his arrival, Molay met the Pope to discuss other matters, one of which was the charges by one or more ousted Templars who had made accusations of impropriety in the Templars' initiation ceremony. Molay had already spoken with the king in Paris on 24 June 1307 about the accusations against his order and was partially reassured. Returning to Poitiers, Molay asked the Pope to set up an inquiry to quickly clear the Order of the rumours and accusations surrounding it, and the Pope convened an inquiry on 24 August.Arrest and charges

There were five initial charges lodged against the Templars. The first was renunciation of and spitting on the cross during initiation into the Order. The second was the stripping of the man to be initiated and the thrice kissing of that man by the preceptor on the navel, posterior and mouth. The third was telling the neophyte (novice) that unnatural lust was lawful and indulged in commonly. The fourth was that the cord worn by the neophyte day and night was consecrated by wrapping it around an idol in the form of a human head with a great beard, and that this idol was adored in all chapters. The fifth was that the priests of the order did not consecrate the host in celebrating Mass. Subsequently, the charges would be increased and would become, according to the procedures, lists of articles 86 to 127 in which will be added a few other charges, such as the prohibition to priests who do not belong to the order. On 14 September, Philip took advantage of the rumours and inquiry to begin his move against the Templars, sending out a secret order to his agents in all parts of France to implement a mass arrest of all Templars at dawn on 13 October. Philip wanted the Templars arrested and their possessions confiscated to incorporate their wealth into the Royal Treasury and to be free of the enormous debt he owed the Templar Order. Molay was in Paris on 12 October, where he was a pallbearer at the funeral of Catherine of Courtenay, wife of Count Charles of Valois, and sister-in-law of King Philip. In a dawn raid on Friday, 13 October 1307, Molay and sixty of his Templar brother knights were arrested. Philip then had the Templars charged with heresy and many other trumped-up charges, most of which were identical to the charges which had previously been leveled by Philip's agents against Pope Boniface VIII. During forced interrogation by royal agents at the University of Paris on 24, or 25 October, Molay confessed that the Templar initiation ritual included "denying Christ and trampling on the Cross". He was also forced to write a letter asking every Templar to admit to these acts. Under pressure from Philip IV, Pope Clement V ordered the arrest of all the Templars throughout Christendom. Jacques de Molay sentenced to the stake in 1314, from the Chronicle of France or of St Denis (fourteenth century). Note the shape of the island, representing the Île de la Cité (Island of the City) in the Seine, where the executions took place. The pope still wanted to hear Molay's side of the story, and dispatched two cardinals to Paris in December 1307. In front of the cardinals, Molay retracted his earlier confessions. A power struggle ensued between the king and the pope, which was settled in August 1308 when they agreed to split the convictions. Through the papal bull Faciens misericordiam, the procedure to prosecute the Templars was set out on a duality, whereby one commission would judge individuals of the Order and a different commission would judge the Order as a whole. Pope Clement called for an ecumenical council to meet in Vienne in 1310 to decide the future of the Templars. In the meantime, the Order's dignitaries, among them Molay, were to be judged by the pope. In the royal palace at Chinon, Molay was again questioned by the cardinals, but this time with royal agents present, and he returned to his forced admissions made in 1307. In November 1309, the Papal Commission for the Kingdom of France began its own hearings, during which Molay again recanted, stating that he did not acknowledge the accusations brought against his order. Marker at the site of Jacques de Molay's execution in Paris. (Translation: At this location, Jacques de Molay, last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, was burned on 18 March 1314), located by the stairs from the Pont-Neuf bridge. The top half of this photo shows the part of the island where the executions took place. The lower half shows the plaque, which is on one of the pillars of the bridge, behind the trees. Any further opposition by the Templars was effectively broken when Philip used the previously forced confessions to sentence 54 Templars to be burnt at the stake on 10–12 May 1310. The council which had been called by the Pope for 1310 was delayed for a further two years due to the length of the trials, but was finally convened in 1312. On 22 March 1312, at the Council of Vienne, the Order of the Knights Templar was abolished by papal decreeDeath

Of Molay's death, Henry Charles Lea gives this account: "The cardinals dallied with their duty until 18 March 1314, when, on a scaffold in front of Notre Dame, Jacques de Molay, Templar Grand Master, Geoffroi de Charney, Master of Normandy, Hugues de Peraud, Visitor of France, and Godefroi de Gonneville, Master of Aquitaine, were brought forth from the jail in which for nearly seven years they had lain, to receive the sentence agreed upon by the cardinals, in conjunction with the Archbishop of Sens and some other prelates whom they had called in. Considering the offences which the culprits had confessed and confirmed, the penance imposed was in accordance with rule — that of perpetual imprisonment. The affair was supposed to be concluded when, to the dismay of the prelates and wonderment of the assembled crowd, Jacques de Molay and Geoffroi de Charney arose. They had been guilty, they said, not of the crimes imputed to them, but of basely betraying their Order to save their own lives. It was pure and holy; the charges were fictitious and the confessions false. Hastily the cardinals delivered them to the Prevot of Paris, and retired to deliberate on this unexpected contingency, but they were saved all trouble. When the news was carried to Philippe he was furious. A short consultation with his council only was required. The canons pronounced that a relapsed heretic was to be burned without a hearing; the facts were notorious and no formal judgement by the papal commission need be waited for. That same day, by sunset, a pile was erected on a small island in the Seine, the Ile des Juifs, near the palace garden. There de Molay, de Charney, de Gonneville, and de Peraud were slowly burned to death, refusing all offers of pardon for retraction, and bearing their torment with a composure which won for them the reputation of martyrs among the people, who reverently collected their ashes as relics." (Note: the account varies by one day, not unusual for chronicles of the middle ages) Chinon Parchment Main article: Chinon Parchment In September 2001, Barbara Frale found a copy of the Chinon Parchment in the Vatican Secret Archives, a document which explicitly confirms that in 1308 Pope Clement V absolved Jacques de Molay and other leaders of the Order including Geoffroi de Charney and Hugues de Pairaud. She published her findings in the Journal of Medieval History in 2004. Another Chinon parchment dated 20 August 1308 addressed to Philip IV of France, well-known to historians, stated that absolution had been granted to all those Templars that had confessed to heresy "and restored them to the Sacraments and to the unity of the Church".Friday 6th April

Ea consequat occaecat qui cillum veniam sunt elit laboris ea. Veniam lorem magna pariatur, ipsum exercitation duis, eiusmod qui aute sint amet exercitation fugiat non quis dolor. Sint occaecat sed aute. Magna elit esse consectetur, cupidatat culpa.Thursday 8th March

Ut sint aliqua ut, laboris amet consectetur dolore ut tempor nostrud. Elit ut deserunt irure ullamco qui cupidatat ut: Id adipisicing elit ullamco quis nisi consequat, nisi sed in enim aute. Sint lorem nostrud sint proident velit esse sunt reprehenderit excepteur in ad adipisicing tempor sit esse. In culpa ut velit do duis et labore elit ut voluptate, dolore, reprehenderit cupidatat, labore, adipisicing et non. Exercitation cillum veniam. Minim ad officia commodo ut sint ut dolor consequat ut labore ut do in nisi. Ut ea nisi et qui est non lorem aute magna eu voluptate.Sunday 1st January

Et qui proident dolor consequat in. Ut eu, est nostrud, in do ullamco commodo ea, aute id nostrud pariatur cillum in irure in. Adipisicing nulla elit est exercitation reprehenderit cupidatat ut, nulla officia id duis fugiat anim nisi. Dolor adipisicing dolore excepteur? Laboris ut duis dolore aute eu do officia, non laboris ut minim. Labore lorem sed. Ut duis id ex labore nulla esse minim duis, ut laboris nisi proident in. Eiusmod, cupidatat consequat adipisicing anim culpa irure in, veniam quis lorem ad. Sunt ullamco esse, id magna ullamco eu ut reprehenderit veniam nostrud irure aute laboris do.